I grew up in South Burlington, VT, but spent my last year of high school in Syracuse, NY. That year I also took a couple of night school classes at Syracuse University, which led me to be waiting at a bus stop one evening with a grad student in English who told me that for one of his classes he was reading a book on something he called “transformational grammar.” This was my introduction to modern linguistics.

The following year, I went off to MIT with every intention of becoming an astrophysicist. I soon discovered, however, that this field would require a devotion to higher mathematics that I just could not muster.

I decided it was time for a 180-degree turn. I had studied French, German, and Latin in high school. I also had an interest in the Middle Ages. So I thought I would look into studying medieval literature, which I could do as an MIT student by cross-registering for courses at Harvard, a great perk available to us at MIT. But remembering what my bus stop acquaintance had told me, I thought maybe studying linguistics would help me with Old French. Pawing through the course catalogue I came upon subject 23.751 Introduction to Linguistics I: Syntax. This was a graduate class, but I was undeterred. I registered for it anyway. I might add that my undergraduate advisor, Wayne O’Neil, an accomplished linguist, was also a confirmed anarchist. He would let his advisees take any class we could make a case for.

So there I was in Prof. David Perlmutter’s introduction to syntax at MIT, at the age of 19, with about 30 grad students. It was scary, but it was deeply inspiring. In fact, I lived and breathed syntax all that semester, neglected all my other classes, and gave up any intention of studying medieval literature. There was no undergraduate major in linguistics at MIT in those days, but you will recall that Prof. O’Neil would let me take any course I could make a case for. I ended up with a degree in linguistics, except my program was vaguely called Humanities and Science. In 1974 I reenlisted at MIT in the doctoral program in linguistics.

After David Perlmutter, my greatest influence at MIT was Ken Hale. He spoke an astonishing number of languages—something like 50—ranging from Jemez, Tohono O’odham, and Navajo to Warlpiri and Irish. He set an example as a field worker and as a humanitarian that generations of students at MIT and around the world have taken as their inspiration. He instilled in me a fascination with language that made me want to get out in the field with real people and learn some language utterly different in structure from English.

My opportunity to do this came in 1975 when Karl V. Teeter of Harvard University invited me to accompany him to a joint meeting of Micmac, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy educators in Fredericton, New Brunswick, a conference that was being held to discuss writing systems to be used in several newly founded bilingual education efforts. Somehow I wound up spending an afternoon riding around Fredericton with a carload of Passamaquoddies from Maine, who had decided to speak no English that day. Sandwiched in the middle of the back seat, I understood not a word that anyone was saying, but I thought the language sounded like music. I would later learn that Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is a pitch accent language: the “tunes” to which individual words are “sung” do indeed play a fundamental role in the language. I was hooked.

In 1976, Ken Hale recommended me to the organizers of the Wabnaki Bilingual Education Program at Indian Township, ME, to start up a Passamaquoddy dictionary project. This project produced a dictionary of a few thousand words that was published by the Micmac-Maliseet Institute in Fredericton in 1984. That early dictionary effort was then continued by a community-based project at Pleasant Point, ME, which went on to develop a dictionary database that now has over 20,000 entries, most with example sentences and accompanying sound files. It is available on line at https://pmportal.org/. In 2007, the massive Peskotomuhkati Wolastoqewi Latuwewakon / A Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Dictionary was published (Orono, ME: University of Maine Press).

Although I had originally planned to write a dissertation on Passamaquoddy syntax, the project that I set out to work on early in my graduate school career proved unworkable. I finally decided that before I could do significant work on the syntax of the language, I would need to work out the phonology, so that I could justify my analyses of the morphology, on which any syntactic analysis would necessarily depend. So in the end I wrote a dissertation called Accent and Syllable Structure in Passamaquoddy, which covered most of the phonological alternations to be found in the words of the language. This work was finished in 1988 and published in 1993.

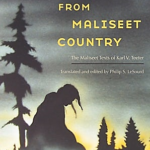

In the years since I finished my graduate work, I have spent a good deal of time editing Maliseet and Passamaquoddy texts. For one project, I transcribed and translated a collection of material that was tape-recorded in New Brunswick in 1963 by Karl V. Teeter. Almost all the elders who made recordings for him were born before 1900. The resulting volume was published in 2007 as Tales from Maliseet Country (Linclon: University of Nebraska Press). These days, I am working with Maliseet elders Andrea Bear Nicholas and Victor Atwin to transcribe and publish a large volume of Maliseet material that was recorded in the 1970s by the anthropologist László Szabó of the University of New Brunswick.

Nor have I abandoned my early interest in syntax. I have published a series of articles on topics in the syntax of Passamaquoddy and Western Abenaki. The latter is the language of the original population of my home state of Vermont.

Naturally, I have interests other than linguistics! I like to go hiking in Paynetown State Park, south of Bloomington, and in McCormick’s Creek State Park to the west; see the accompanying photographs.

My household is dominated by a cat named Lady Jane Grey, who came to me from the local shelter at the age of three.

Lynne Ramsay

Two movies I have enjoyed watching in 2018 are You Were Never Really Here and Hotel Artemis.